Steam Power in Colorado’s Sugar Factories

Show on map November 20th, 2007

Show on map November 20th, 2007

By Jonathan H

These Detroit Rotograte Stokers work great at continuously discharging ash from the burning of coal. These stokers at the Great Western’s Longmont refinery were part of a much larger system of boilers that fed steam power for the entire factory (photo copyright Jon Haeber).

Editor’s Note: This is the final section of the series, “Sugar Refineries in Colorado.” See part 1 here and part 2 here. It’s recommended that you read part 1 and part 2 before beginning with this section.

Sugar refineries in Colorado were powered by steam. The most popular steam boiler of choice for these factories were the Babcock and Wilcox water-tube boilers — revolutionary and efficient steam creators for their time. The power house of the factories featured a monumental array of ten massive boilers — all of which required incredibly coordinated logistical fueling using a continuous supply of coal. This was not done by manpower– everything was mechanized. Railroad cars delivered the coal, it was crushed into one-inch chunks, brought in by conveyence to mechanical stokers, burned, discarded through flumes, and finally exited as ash.

Sugar refineries in Colorado were powered by steam. The most popular steam boiler of choice for these factories were the Babcock and Wilcox water-tube boilers — revolutionary and efficient steam creators for their time. The power house of the factories featured a monumental array of ten massive boilers — all of which required incredibly coordinated logistical fueling using a continuous supply of coal. This was not done by manpower– everything was mechanized. Railroad cars delivered the coal, it was crushed into one-inch chunks, brought in by conveyence to mechanical stokers, burned, discarded through flumes, and finally exited as ash.

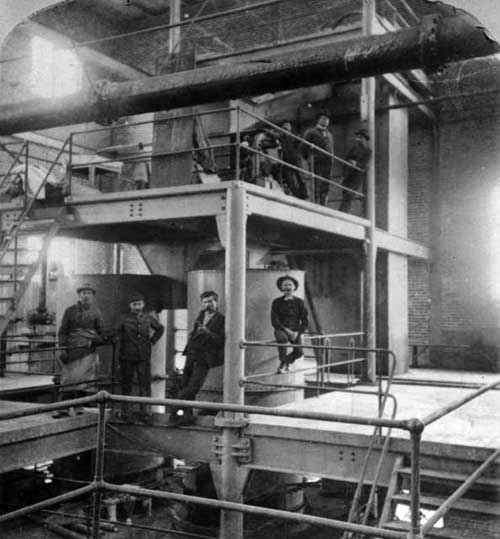

Men stand near the cossette slicing machine at Eaton, Colorado ca. 1910 (courtesy Denver Public Library).

This incredible steam power was utilized throughout the factories’ multiple rooms and corridors through a complex system of drive-shafts. workers could engage or disengage shafts through a series of levers and belt-transfer guides. Despite its incredible, 3,000 horsepower system of steam strength, these factories still employed 300-500 workers of various tasks — even their own chemistry and assay departments to measure the sugar content of incoming beets.

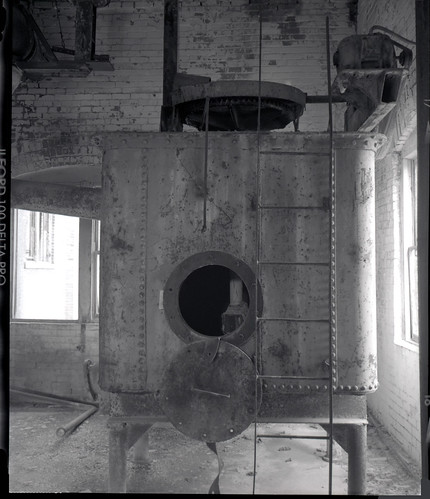

This box shaped contraption at the Longmont sugar refinery perplexed me, but I could only assume that it was pressurized, as indicated by the rivets and portholes (photo copyright Jon Haeber).

Corporate Consolidation of Sugar: A Massive Industry

Indeed, sugar in the eastern foothills of the Rockies was far from a small-town cottage industry. William May, who wrote The Great Western Sugarlands, claims that Colorado’s sugar industry produced more revenue than mining in the state. Combine the rich sugar content of Colorado’s beets with government-provided bounty for domestic producers of sugar — add the lynchpin of it all, the Dingley Act of 1897 (which levied a heavy tax on foreign sugar) — and you’ve got the perfect storm for a boom in beet production.

The factory at Eaton, CO. Notice the effluence coming from the smokestack. This is the lime kiln. The boiler house is outside of view from the image (photo courtesy Denver Public Library).

It was a perfect storm that was ripe for H.O. Havemeyer’s picking. Havemeyer did this as tactfully as any robber-baron could: through an extremely complicated system of acquisitions and alliances using his American Sugar Company Trust. As Eric Twitty in Silver Wedge so aply puts it, the trust “converted the Colorado sugar industry into a coordinated sugar-manufacturing machine, which it loosely balanced with its sugar sources elsewhere in the United States,” among which included half of Spreckels stake in sugar from Hawaii and California.

The Great Western Sugar Company fell victim to the growth of artificial sweeteners, foreign imports, and the dissolution of government subsidies. Only a few select sugar refineries in Colorado remain in operation (Photo copyright Jon Haeber).

Eventually, however, even corporate consolidation and efficiencies couldn’t mean the continued survival of an outdated commodity source. One by one, the factories across Colorado closed down. Corporate neglect may have partly been the reason, but it ultimately became simple geography. Once artificial sweeteners, sugarcane, and corn syrup took their stranglehold on the American sweetening industry sugar beets became a thing of the past. By 1985, all but one of Colorado’s grand sugar refineries had shuttered.

The workshop at Eaton Refinery. If you want esoterica, look no further than this workshop at Eaton’s sugar refinery. Here, were a number of whos-its and whats-its galore. One could only wonder what the worker in this workshop did in a typical day. No doubt there are plenty of opportunities for idle tinkering (Photo copyright Jon Haeber).

Further Reading on the Sugar Factories of Colorado

Silver Wedge: The Sugar Beet Industry in Fort Collins

http://www.ci.fort-collins.co.us/historicpreservation/pdf/sugar-beet-industry-doc.pdf

Historic Markers of Colorado — History of Sugar Beets in the State

http://www.coloradohistory.org/ripsigns/show_markertext.asp?id=825

Suspicious Monopolistic Agreement Between Great Western and H.O. Hevemeyer

http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9507EED9153CE633A25757C0A9609C946396D6CF