| << Previous -- Index -- Next >> | ||||||

| Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 |

CHAPTER VI

GETTING THINGS AND GOING PLACES: 1920-1940

Figure 30: Pluto Advertisement, 1918

“I passed Morton's every day on my way home from school but never stopped before this window until one day I was shocked into attention by a glint of red from the window. I stopped and stared. There in the midst of all the dinginess and drabness was a beautiful red devil, a devil fully equipped with horns, forked tail, pitchfork and a startling sneer. He stood on a cardboard stand labeled Pluto Water. I wanted him immediately, but I could think of no way of getting him that would seem respectable… Every day, I visited the window. The glamour and glitter of the other window seemed superficial now, and every day I tried to think up respectable lies that would make him mine.”

– Ellen (Mary Doyle Curran) in Paper City

Mary Doyle Curran was born in 1917, almost a decade after Jacques Ducharme, but it may as well have been a generation. Upon her birth, all of Holyoke’s theatres (even the Franco-American venues for troupes) had been converted to motion picture venues; the earliest affordable radios were about to be sold; the Model T was available to the new middle class consumers thanks in part to changes in the availability of installment credit; and Steiger’s emerged from the war with twice the sales it had in 1915 (Figure 31).

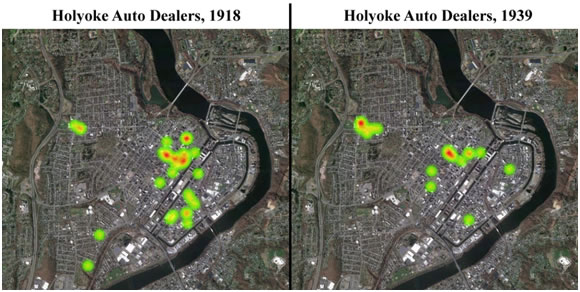

Figure 31: Holyoke Auto Dealerships, 1918-1939

The map above shows the density and distribution of auto dealerships. From their early growth in the teens and twenties, dealerships located overwhelmingly above High Street. After the Great Depression, only the dealers attached to national brands could compete, and they were entirely above High Street.[152]

Most significantly, mass marketing was finally emerging as a profession and became a rising force after distancing itself from the stigma of patent medicines.[153] Nationally, advertising in periodicals rose from $54,000,000 to $320,000,000 between 1909 and 1929. Newspaper advertising was just as dramatic, going from $149,000,000 to $729,000,000 – significant because it reflects the growing influence of national brands in local publications.[154] In fact, one year before Mary’s birth, the Holyoke Transcript-Telegram featured ads for Wrigley’s spearmint gum, Armour packaged foods, and H-O Oatmeal (Figure 32).

Figure 32: National brands in Holyoke’s Publications and Streets

Wrigley’s gum, Armour packed meats, and H-O oatmeal – all nationally advertised goods appearing in the Transcript-Telegram, October, 1916 (top); On High Street, ca. 1920, a billboard advertised the costs for Studebakers while motion picture advertisements and Coca-Cola occupy the right and left of the image (bottom)

Brands started to become part of the local discourse. On July 1, 1931, a truck with an advertisement for Wrigley’s bubble gum printed on the side pulled up to the offices of the Holyoke Water Power Co.[155] Employees reported in Steiger’s Store News that an epidemic of “Forditis” was spreading among its shipping department and clerks.[156] The American Writing Paper Company employee newsletter mentioned that a machine tender named Murray was thinking about buying a Ford; the newsletter snidely responded: “Thinking about buying a Ford? How about a baby grand?” (Figure 32).[157]

More than was the case with Ducharme, Doyle Curran was born into a society of consumers, and her written works reflect misgivings about its consequences. Her two works on Holyoke, Parish and the Hill, as well as her unpublished manuscript, Paper City, dwell on the theme of death – death in all of its manifestations, but especially the death of the city and its traditions, its communal ties broken apart by acquisitive people “making and getting, and ‘going places.’”[158] Though her story is about death, she was witnessing the birth of a culture that Holyoke had always lacked until then: a large middle class with disposable income. If we take Worcester as a rough proxy for Holyoke, Rosenzweig noted that at least 15 to 20 percent of the city's Swedes, Irish, and French Canadians had achieved the middle class level by 1915 – an income that was pegged on the low end at $1,000 to $1,200 a year for a family of five – enough to get by with a modest surplus for saving or spending on sundries.[159]

Efforts to Track Worker Budgets in Holyoke, 1919-1930

In response to labor disputes, changing taxes on consumer goods, and the First World War manufacturers began collecting budget studies of their employees. John Scoville, a statistician for American Writing Paper Company (AWP), looked at the cost of living in Holyoke in 1919. He asserted that government figures did not reflect the actual conditions in Holyoke. His estimates showed a 72.5% increase in the cost of living since 1913, as opposed to the government’s national estimate of 102%.[160] Scoville was not without an agenda, though. AWP endeavored to justify either modest wage increases or none at all. Earlier, the company conceded to a series of increases due to wartime labor shortages and inflation, but when Scoville completed his study in 1919, the company was eager to freeze increases once it could back them up with data that proved workers were adequately paid. The employees did not appear to be too pleased; The Eagle A newsletter made a derisive comment in an article entitled “The World Will Come to an End When…” which stated among other things, “We can live according to Mr. S-----‘s statistics. (We wonder if he means Sawdust?).”[161] The reference to sawdust may have been alluding to Scoville’s estimates for the costs of heating or tobacco – cheap tobacco was known as “sawdust” and actual sawdust was a cheaper, though much less effective form of heating than coal. It could have also been an allusion to Upton Sinclair’s account in the Jungle, where sawdust and rats were used as filler by the meatpacking industry. Whatever the case, it was an underhanded jab.

Instead of wage increases, AWP appeared to be interested in an impressively sophisticated welfare capitalism organization that included basketball teams, dedicated social spaces in the Hotel Hamilton, minstrel shows, trips to amusement parks, company newsletters, and a full-time, company-appointed labor liaison.[162] On the whole, Holyoke had a vibrant welfare capitalism apparatus set up by the mid-1920s. Doyle Curran’s father worked at the Farr Alpaca mills, which provided an auditorium, had its own marching band, sold food and sundries in its factory-based cooperative at cut-rate prices, and was one of the first mills in Holyoke to have its own in-factory hospital. Farr Alpaca was also revolutionary in instituting a profit sharing plan.[163]

When it comes to the estimated expenditures by households for categories of needs, the Bureau of Labor Statistics budget estimates concur with the figures provided by Scoville for Holyoke residents: Food (43%), Rent (18%), Fuel & Light (6%), Clothing (13%), Sundries (20%.) The key items of concern for employers and moralists alike were the sundries because they were the most opaque expense. During the war years there was a resurgence of concern over profligacy, culminating in the Armistice. The brief moments after the war (and the end of the flu pandemic) resulted in what moralist Bruce Barton called an ‘orgy of extravagance,’ a spending binge that Horowitz believes was caused in part by runaway inflation’s effects on saving habits. On the heels of the war, the federal government conducted an unprecedented study of household budgets. The findings showed a large increase in sundry expenses; during Carroll Wright’s study of 1875, most families only spent 3 to 10 percent of their budget on such expenses. By 1918-1919, around one-fourth of a family’s budget went to miscellaneous expenses, and they went to a much wider range of items, from life insurance, to church, gifts, streetcar fare, movies, newspapers, postage, barbers, etc.[164] Scoville uses some of the same categories in his study of Holyoke families. The resulting choices reveal inflation’s impacts on expenses for Holyoke’s working class residents, but – more importantly – the types of expenses that AWP was concerned with tracking (Table 2).

Table 2: Sundry Expenses for Holyoke Workers, 1913-1919

Sundry |

1913 |

1919 |

Increase % |

Shave |

0.1 |

0.15 |

50.00% |

Hair cut |

0.25 |

0.35 |

40.00% |

Trolley fare |

0.05 |

0.07 |

40.00% |

Tooth filled |

1 |

1.5 |

50.00% |

Doctor's call |

1 |

2 |

100.00% |

Movie ticket |

0.1 |

0.22 |

120.00% |

Collar laundered |

0.02 |

0.04 |

100.00% |

Transcript |

0.01 |

0.02 |

100.00% |

Postage stamps |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.00% |

3 Kaffir cigars |

0.25 |

0.35 |

40.00% |

1 pound nails |

0.05 |

0.08 |

60.00% |

Telephone, 1 year |

2.5 |

2.75 |

10.00% |

100 lbs ice |

0.4 |

0.6 |

50.00% |

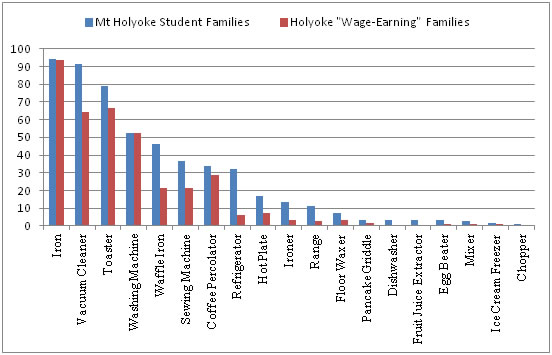

Scoville’s study was followed up in the 1930s with an extensive series of investigations by Mount Holyoke College students under the auspices of Amy Hewes. The studies that Hewes’ students conducted reflected the key changes that occurred in the decade from 1920 to 1930 – namely the widespread adoption of electrical appliances. The report, “Electrical Appliances in the Home” surveyed 764 families of Mt Holyoke College students and 201 women in wage-earning families living in Holyoke.[165] The Mt Holyoke contingent was from families with significantly higher incomes than the Holyoke contingent. For that reason, the percentages for each household type were compared (Figure 33).

Figure 33: Electrical Appliances in the Home, 1929

It should be noted that the Hewes study inadvertently focused on households that were actively interested in the ideals of domesticity, which – by the 1920s – called for the scientific management of the home through consumer goods. The women surveyed by the students in Holyoke were part of the Holyoke Home Information Center, which was incorporated in 1926 to teach home skills to new immigrants. These were women who were receptive and more likely to be early adopters of consumer goods. A 1920s photo suggests they were the more ardent of consumers among wage-earners in Holyoke. In fact, some of the coats could have probably been found on the racks of Steiger’s (Figure 34). Despite its shortcomings, the survey still provides a valuable glimpse into the prevalence of certain household goods among a segment of Holyoke’s wage-earning population.

Figure 34: Holyoke Home Information Center, ca. 1920s

A close look at the data reveals that the poorer women in the Holyoke segment were more likely to own electrical cleaning appliances at the same rate as the wealthier households. The washing machine and iron had the highest adoption rate, whereas the refrigerator and waffle iron were among the lowest. The high adoption rate of cleaning appliances perhaps reflects the preferences of these families in the 1920s – these appliances allowed for social distinction through the care of clothing and home; only after maintaining a clean home could wage-earning consumers then focus on improving the efficiency of providing food on the table. As William Jenkins notes in his study of Buffalo’s upwardly mobile Irish Americans: “Patterns of house visiting tested the housekeeping abilities and fashion tastes of [Buffalo’s] parish women, subtly reinforcing a pervasive bourgeois ethos blandly outlined in the advice columns of the Union and Times but reproduced in livelier fashion through advertisements in daily newspapers and actively through conversation and gossip.”[166] Wage-earning households did not have to contend with the proverbial “servant problem,” but cleaning appliances still helped make a house appear as if it had a servant, even if a wage-earner could not afford one. Of course, the low adoption rate of the electrical sewing machine confounds that conclusion. The sewing machine anomaly may be explained by the higher willingness of wage-earners to buy ready-to-wear clothes.[167] In any case, the high adoption rates of electrical appliances as a whole among the Holyoke women indicates their embrace of modern consumer goods. The question now remains: How do the family practices in Doyle Curran’s writing coincide with the on-the-ground data gathered by Hewes and Scoville? In order to answer that question, we will examine character interactions with consumer goodsin both Paper City and Parish and the Hill.

Divisions at the Irish-American Threshold

Irish Americans were initiated into modern consumer society sooner than other working class groups in Holyoke. Much of this had to do with the economic prosperity of the Irish, who gained a foothold in city politics as early as the 1880s and maintained a plurality in the police force, teaching, and firefighting professions.[168] A second factor was the geographic orientation of the Irish, who were concentrated above the second level canal and had much more frequent interaction with the commercial life of High Street than that of Main Street. Finally, the Irish had the advantage of speaking English, and much of the media – especially the mass media – was oriented towards Native English speakers.

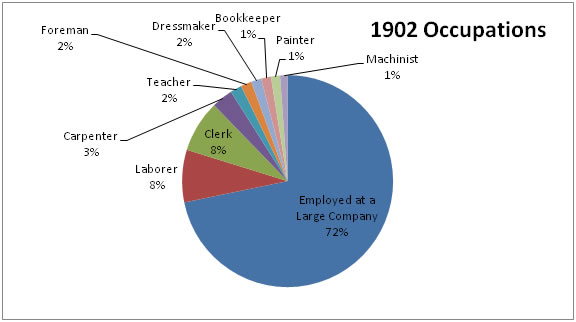

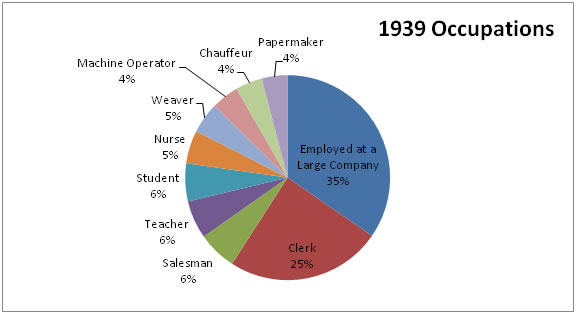

Like Ducharme, Doyle Curran’s characters, by and large, are based on real people. The places where the characters of Mary and Ellen live (protagonists of Parish and Paper City respectively) are the same places that Mary Doyle lived as a child.[169] In many ways, the occupations and family organization of the Doyles typify the Irish American experience in Holyoke – Mary’s brothers (both in real-life and the novel) work as clerks, rather than in the mills, representing the occupational shift that occurred in the early 20th century (Figure 35). Mary’s mother, like many Irish families, did not work outside of the home. Lastly, the gradual migration from “The Patch,” the area that once held the makeshift shacks, to the nearby tenements, and finally to “The Hill” was a common trajectory for many immigrants in Holyoke; by the 1940 census, 23 percent of the foreign-born residents lived in the two wards that made up “The Hill.”[170]

The principal characters in Parish and the Hill include Mary’s grandfather, John O’Sullivan; Mary’s mother, Mamie O’Connor; Mary’s father, James O’Connor; brothers, Eddie, Michael and Tabby; and a series of different aunts and uncles who play varied roles of importance. Paper City’s principal characters are essentially the same, but with different names. Mary’s grandfather plays a role not unlike Cecile in The Delusson Family – he maintains close ties to his heritage and is most ardently against the culture of acquisitiveness and distinction that began to arise among Irish who lived on “The Hill.”

Figure 35: Top Ten Occupations in Holyoke, 1902 and 1939

The occupational data was culled from the Holyoke city directories of 1902 and 1939, which listed employment. The figures above not only illustrate the changing diversity of occupations in Holyoke, but also the drop in employees at large companies such as factories and the rise of clerks and salesmen (consumer-oriented occupations).

Mary’s father is most willing to leave his past behind him – a fact which is partly attributed to his background as a County Cork Irishman as opposed to a Kerry Irishman. Mary’s brothers and uncles respond to their divided ethnic loyalties in various ways. On the two extreme poles are Mary’s uncle, Smiley and her brother, Tabby. Tabby embraces consumer culture and goes on extravagant spending binges. Her uncle, Smiley is a staunch Irish Nationalist with a flair for Fenian bravado – best exemplified by the moment when he sings the Irish national anthem in front of a crowd of respectable Yankees at the Opera House. [171]

The divide within the O’Connor family is not only across generations, but also within the same generation. In the beginning of Parish, there is a vivid moment when Mary is caught between deciding whether to follow her mother or her father. The “threshold” moment not only tells of a crisis of ethnic self, but also a crisis between the embrace of modernity by her father and the traditions of her mother: “I remember standing in a doorway with my father pulling me one way and my mother the other. Full of pain and panic, I wondered why neither would cross the threshold. With the clear logic of a child, I realized that I could not go both ways.”[172] In some ways this crisis is similar to the crisis that Ducharme presents in his advocacy for survivance, but in other ways it is entirely distinct. Mary’s crisis not only comes in the midst of an era of immigration restriction and Americanization efforts, but also an era of a mature, established consumer culture. The ways in which the Delussons and O’Connors cope with modernity as consumers tells a lot about the influence of consumer capitalism on the daily practices of Holyokers and the changing nature of these practices from 1900 - 1940 (Table 3).

The O’Connors as Consumers

Early in Parish and the Hill, Mary’s father is depicted as a cigar smoker, but by the Great Depression he smokes cigarettes; Jean-Baptiste, on the other hand, is always smoking a pipe. Relli Shechter’s fascinating study of smoking and modernity describes cigarettes as the ultimate symbol of the new consumer culture. Fast, efficient, and portable, cigarettes provided a rising middle class (Egypt’s effendi in Shechter’s account) the ability to mix work and leisure while displaying their status; Shechter finds that pipes, on the other hand, were considered to be items of tradition and ‘backwardness’ – the type of consumption that expended more leisure time than was necessary.[173]

Table 3: Interactions with Consumer Goods in Accounts by Ducharme and Curran

Consumer Good |

Delusson Family (1874 -1910) |

Parish/Paper City (1920-1940) |

Tobacco |

Jean Baptiste ca. 1870 - uses a pipe to smoke tobacco (164) |

Mary's father uses cigarettes in the Great Depression (113, Parish) |

Print Media |

Jean reads local newspaper; Cecile reads French-language newspaper (157, 164, 180) |

Mary's father reads Atlantic Monthly; mother reads Transcript-Telegram (86, Parish) |

Furniture |

Furniture was heirloom, which had to be sold in the trip to the U.S. Upon move to Granby, the family purchases second-hand furniture (264) |

Front rooms of Irish tenements were "filled with heavy furniture, bought at the local furniture store" (2, Parish) |

Radios |

N/A |

Mary's father obsessively listens to stock market reports on radio (113, Parish); Tabby listens to Father Charles Coughlin (180, Parish) |

Automobile |

The first time a vehicle appears in the story is the honeymoon for Anne Dulhut and Pierre Delusson (250) |

Tabby drives an expensive car: "What do you mean get nowhere! Look at me. I'm on top, seventy-five bucks a week, a car, plenty of clothes (216, Parish) |

Confectionary |

Pierre "had never been in a bank, and money was a nickel or ten cents, which sometimes he had to spend for candy" (120) |

Mary gives Polish children in Kerry Park some of her candy; grandfather returns home and despairs at the sense of ownership (25, Parish) |

Department Store Goods |

Early in the story, Cecile frequently sews (7-8, 45, 56). Then childrens' clothes are bought ready-made at Dulhut's store (137). By the end of the novel, characters are judged by their clothes. |

Mrs Reardon “loved, righteously, to forage through the better department stores” (101, Paper) |

Provisions |

“Marchesseault’s grocery store had the character of a general store. One could buy any article there, and best of all, one could obtain credit, if money were lacking” (42) |

"For nothing was bought by the five pounds. The flour was bought in barrels, the potatoes in huge rag bags” (9, Paper) |

Drug Stores |

Family doctor prescribes a stimulant, but there are no interactions with pharmacies or drugstores in the story (194-195) |

Ellen sees a Pluto Water display in Morton's drug store and is enchanted by it. Receives it in reward for being honest, but it eventually ends up becoming an idol (53-57, Paper). |

The second example has to do with the consumption of print media. In The Delusson Family, Cecile reads the French-language press, and even has it sent from Canada by her daughter, Louise. On the other hand, by the time Mary is young her father reads a national magazine (Atlantic Monthly), while her mother is a regular enthusiast of the Transcript-Telegram. As demonstrated in Figure 32, consumer goods produced by large and impersonal corporations were regularly appearing in the local paper, which would differ markedly from the types of ads Cecile would have seen in her Quebec papers. The hybrid local-national imagined community that the Transcript-Telgram inculcated into readers intermixed news about births, deaths, marriages, and social events with visually stunning depictions of packaged goods, idealistic domesticity, and quick fixes to modern life’s woes – all offered by distant producers.

Radios do not appear in The Delusson Family simply because consumer radios were not widely available at the time. However, in Parish and the Hill and Paper City, radio plays a central role at key moments in the narrative. In Paper City, Ted Fuller, a romantic interest of Ellen goes from being a ham radio operator to a “ham business-man.” When they reunite years later in California, he is somebody Ellen does not recognize, as he spouts off stock tips and talks of “progress.” Thus the radio initiates Ted into the life of a technocrat businessman who could only talk stocks and H-bombs – “the waste of a blue-eyed boy – gentle and sweet man whom I had once loved. Lonely beyond loneliness, I knew very well how lonely he was.”[174] Similarly, in Parish and the Hill, Mary’s father becomes obsessed with listening to stock tips on the radio. As her father’s stock investment tumbled, she writes, “somehow this mill worker, poor, one of poor millions, considered himself involved actively in the rise and fall of the vast American market.”[175] Her brother, Tabby, the fast-talking opportunist who drives expensive cars, becomes enamored with Father Coughlin over the radio.[176]

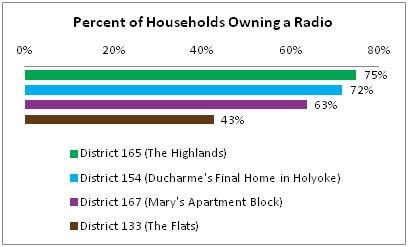

As mediator between outside, cosmopolitan culture and the insularity of the parish, radio had a profound effect on Holyoke’s working class consumer patterns. But Liz Cohen concludes that radio also helped reinforce and maintain connection to ethnic, working-class life in the midst of an impersonal outside world – especially in its early growth phase; thus Holyoke’s Franco-American community was treated to a weekly “French Hour,” family members listened to the radio together, and labor organizations used radio to strengthen their movements. It was not until the Congressional Radio Act of 1927 that large networks began to dominate the airwaves and mass advertising became part of that growth.[177] Did Holyoke follow national trends in radio adoption? More importantly, did the working class neighborhoods become part of radio culture to the same extent as the middle class? The 1930 census helps us speculate on possible answers to those questions.

A total of 5820 individuals in four separate census enumeration districts (EDs) were extracted and compiled. Each ED corresponded with a neighborhood that was inhabited by the authors or their characters (as indicated in descriptions from the novels). District 165 (1722 individuals) was where Ducharme grew up as a child in the Highlands – a wealthy area where factory owners and executives lived. Mary, in Parish, also called this area cave canem – off limits for a girl like her.[178] District 154 (1235 individuals) was where Ducharme’s mother and sister finally settled after Ducharme left home and attended college; this area, though not quite as “exclusive” as the Highlands was still middle-upper class and was within a few blocks from Wistariahurst and other large mansions. District 167 (835 individuals) contained the main apartment block where Doyle Curran lived, as well as the areas she describes in both Parish and Paper. This was an apartment block not quite within the Highlands but also well out of the working class Patch. It marked an upward social step for her family and it was there that she faced her “threshold” decision. Finally, District 133 (2028 individuals) was largely French Canadian and in the heart of the ward 2 enclave in the Flats.

Because of the high number of multi-family addresses, radio ownership cannot be easily mapped or visualized by address. A map is only helpful in illustrating where the districts are located – 165 (green), 167 (pink), 154 (blue), and 133 (brown) (Figure 36). The data itself has been tabulated by district to show the proportion of households owning a radio set (Figure 37).

Figure 36: Census Districts that Were Mapped for Radio Ownership

District 167 (pink), District 111 (blue), District 154 (brown), and District 165 (green). Each represents a different ethnic or socioeconomic cross-section in the books by Ducharme and Curran. Red dots indicate a street address with a radio, and yellow dots are addresses without radios. Wards are labeled in red.

Figure 37: Percent of Households Owning a Radio in Holyoke, 1930

Doyle Curran’s ED 167 had a 63 percent rate of radio ownership. By national standards, this is well above the 40 percent average. By Massachusetts standards, it stands within the average rate for large cities; Springfield, for example, had an overall adoption rate of 61 percent, while Worcester’s was 60.[179] However, by filtering the list to only account for foreign-born residents who were born in Ireland, the number jumps to 70.5 percent; if one filters that list for children born of either an Irish-born mother or Irish-born father, the number jumps further, to 73 percent – a full 10 percent above the average in ED 167. This trend points to a desire on the part of Irish-Americans to adapt to mainstream society and initiate themselves into new consumer practices – even more than their Yankee counterparts (New England-born heads of household in the same district only had a 67 percent adoption rate).[180] Doyle Curran’s father, Edward Doyle, personifies the eager, working class participant in mainstream consumer society.

Conversely, ED 133, where Ducharme’s grandfather, Etienne first lived when he immigrated to the U.S. (and where Jean-Baptiste first resides in the novel) had a 43 percent ownership rate – almost half that of the Highlands. This is still in line with an urban neighborhood comprised of a large foreign-born population. In fact, 48 percent of the foreign-born White residents in Springfield and Worcester owned radio sets. The five percent lower rate in ED 133 could mostly be attributed to the fact that Precious Blood housed a large number of nuns (none of whom appeared to own radios and each one appears to be counted as an individual head of household). Suffice to say, this is especially high for a community whose principal language was French.

Overall, Holyoke was ahead of the nation (and certainly ahead of the South) in radio adoption. This is significant for a population that is above average in its foreign-born residents. For the fifteenth census, Massachusetts had one of the highest adoption rates in the nation, but it does not necessarily mean that families like the Doyles were opening their arms to the products pushed by radio advertisements.

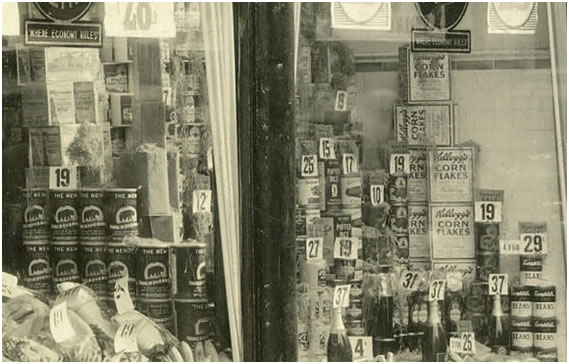

Figure 38: A&P Shop Window on 343 Main, Holyoke, ca. 1930

In 1923, the A&P Gypsies, a musical ensemble that promoted A&P chain store products, became one of the first large-scale, corporate-sponsored radio shows. The window above demonstrates the prevalence of packaged and branded goods in Holyoke’s Franco-American community by the early 1930s. This image was taken at an A&P that is just steps away from the movie theater in Figure 19.

Although the A&P “Gypsies” offered “exotic music with a nomadic motif” as early as 1923 while promoting the store’s packaged brands, it appears the Doyles still went to the corner grocer. Doyle Curran mentions that “nothing was bought by the five pounds. The flour was bought in barrels, the potatoes in huge rag bags.”[181] Despite the resistance of the Doyles to adopting national chains like A&P, such stores were becoming extremely common in Holyoke, and along with them elaborately packaged products (Figure 38). How did such chains alter the city’s landscape and its independent grocers? A brief look at a case study of a grocer in Holyoke is worth examining.

Mary Marconi and the A&P

In 1988, Mary Marconi spoke with Chris Howard Bailey from her home in ward 2 at 298 Race Street. Mary came to the United States from Italy in 1915 when her brother, who owned a grocery store, needed extra help while he worked at a nearby brickyard. In October of 1917, they moved the market to the corner of Main and Appleton, where it remained until 1948, after which they moved to a nearby space with attached apartments that they rented out. Mary was married twice and had one son. When she first came to the U.S. she lived at 238 Race, but she – along with the other tenants – were evicted in 1916. Her family next purchased a home on Appleton Street, but they were evicted again. “The land it was belong to the city. So we have to move again. Because they want the house. They want to eh tear down the house. They build a mill there, where they play ball or something I don’t know. So we have to… buy something, eh solid so they can’t throw us out agin [chuckles]. So we bought this house in 1923.”[182] Mary lived in the home on 298 Race until her death in 1995, and her memories never extended beyond the four-block radius of Main and Spring Street in ward 2.

When Moroni’s Market started, it dealt strictly in dry goods. When they moved to the 274 Main Street location, however, they had a refrigerated room and hired a butcher who spoke French. After moving to 274 Main, a sales representative provided them with a $4,000 loan to stock their store. Mary told Chris Bailey: “We had a man, from New York, he come in… he was a salesman. The one they go around you know. Like my son now he’s a salesman… So then, then he comes in, he go [feet] on us. He filled up our store… Then little by little all this salesman coming in and you can put this in, you can put this in, and everything. And that guy, he trust us for four thousand dollar.”

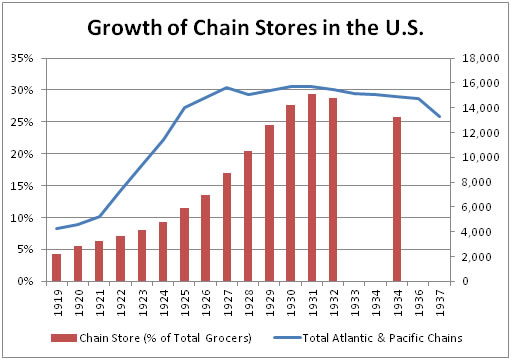

Figure 39: Growth of Chain Grocery Stores in the U.S., 1919-1937

Between 1919 and 1937, Atlantic & Pacific reached a height of 15,700 stores in the U.S., while chain grocery stores overall started the depression controlling 30% of the market (adapted from Ellickson, 6).

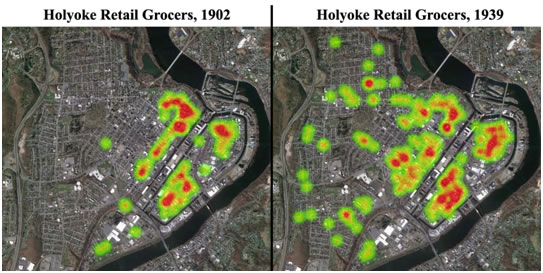

Figure 40: Density Map of Holyoke's Retail Grocers from 1902-1939

With the loan, Moroni’s was able to transition to packaged goods and modernize their store, thanks in part to the backing of the salesman from New York.

Moroni’s was fortunate to survive the 1920s and 1930s. Between 1919 and 1932, the top 5 grocery firms went from controlling 4.2 percent of the market to 28.8 percent (Figure 39).[183] During that same time period, Holyoke went from 6 Atlantic & Pacific (A&P) chain stores to 22, essentially matching the 365 percent growth rate of A&P stores nationwide. The impact on Holyoke grocery stores was enormous. Independent grocers went out of business and moved to other industries, and the surviving grocers spread out of the enclave and atomized into the Highlands (Figure 40). The Census of Distribution indicates that Holyoke went from 155 to 87 retail grocers (without fresh meats) between 1930 and 1939.[184] Most merchants whose address was taken over by A&P moved on to other occupations or locations (Table 4). Mary thinks Moroni’s survived because she offered credit and delivered; in fact, on Sundays, she delivered to peddlers who had squatters’ shacks in the woods. Still, she noted that the Great Depression “was hard. But we had good customer. We had good people. We trust them. And they pay for, when they work you know. People they were really honest… Lot of them, lot of them they still owe us, but good-bye… When we close the store I burn everything what they owe me, I burned everything. I don’t need anything.”[185] Mary’s decision to burn the credit records provides a touching example of the types of reciprocity between grocer and customer that occurred prior to the onslaught of chain stores and supermarkets.

Table 4: Merchants Whose Stores Were Occupied by A&P

Addre ss |

1902 |

1918 |

1939 |

Notes |

1375 Dwight |

n/a |

Adelard C Menard |

A&P |

In 1932, Menard became an independent owner of a butcher shop at 73 Hamsphire Street |

1739 Northampton |

n/a |

n/a |

A&P |

|

377 Main |

Abraham Levine Gents Clothing |

Abraham Levine Gents Clothing |

A&P |

In 1935, Levine moved to 453 Main and became an independent dry goods store owner. By 1940, he was listed as a "collector." |

418 Appleton |

n/a |

Lucius Person |

A&P |

In 1920, Person was employed at The Drapery Shop - 237 Maple St. |

453 High |

n/a |

Jacob Scolnik Coat and Apron Supply |

A&P |

Unknown, no longer lives in city. |

506 South |

n/a |

A&P |

A&P |

|

51 Ely |

n/a |

Sabastien Yenlin, Baker |

A&P |

Yenlin owned two bakeries at 51 Ely and 72 Cabot in 1919, but by 1921 he only owned 72 Cabot. Lived at 107 Clemente |

737 Dwight |

n/a |

Barger Abraham, Grocery & Dry Goods |

A&P |

Abraham Barger became an insurance agent in 1919. |

76 Hampshire |

n/a |

Eva Boulerice |

A&P |

Unknown, no longer lives in city. |

908-910 Hampden |

n/a |

A&P |

A&P |

|

500 South |

n/a |

n/a |

A&P |

|

329 High |

A&P |

A&P |

Dress Shop |

|

137 High |

n/a |

A&P |

n/a |

|

60 Center |

n/a |

A&P |

n/a |

|

265 Main |

n/a |

A&P |

n/a |

Despite being Italian and speaking no French, Mary was determined to embed herself in the culture of ward 2 and, after much persuasion, convinced Precious Blood to finally take her in as a parishioner (though they were reticent at first). Mary eventually picked up French and English as she adapted to life in ward 2. By the 1950s, Pat’s – a cash-and-carry supermarket – moved in down the street and affected her business. By 1968, Moroni’s closed entirely and Mary retired.

| << Previous -- Index -- Next >> | ||||||

| Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 |

[152] Holyoke, Massachusetts City Directory (New Haven, Conn.: Price & Lee Company, 1918), 929–931; Holyoke, Massachusetts City Directory (New Haven, Conn.: Price & Lee Company, 1939), 66.

[153] Marchand, Advertising the American Dream, 25.

[154] Robert S. Lynd, “The People as Consumers,” in Recent Social Trends in the United States: Report of the President’s Research Committee on Social Trends, ed. Wesley Mitchell (McGraw-Hill Book Company, inc., 1933), 871.

[155] Joshua Root, “Fight Town: A Ringside Perspective on Class, Immigration, and Conflict in the Paper City,” 2011, 143.

[156] Harold A Dudgeon, “Holyoke Store News,” Steiger Store News, April 1926, 3.

[157] “American Writing Paper Company Records, 1851-1960,” MS 62, accessed October 6, 2012, http://www.library.umass.edu/spcoll/ead/mums062.html.

[158] Curran, “Paper City,” 50.

[159] Horowitz, The Morality of Spending, 94.

[160] John W Scoville and American Writing Paper Company, Cost of Living in Holyoke, Massachusetts, July, 1919 (Holyoke, Mass.: Reprinted by the Company, 1919).

[161] “The World Will Come to an End When,” Eagle A Unity, December 1919, 52.

[162] Cf. “American Writing Paper Company Records, 1851-1960,” Text, accessed October 6, 2012, http://www.library.umass.edu/spcoll/ead/mums062.html. Unfortunately, the fascinating history of AWP’s foray into company paternalism cannot be covered in full here, but the extensive records at the University of Massachusetts Special Collections contain a trove of publications and notes on these policies.

[163] Frances Cornwall Hutner, The Farr Alpaca Company; a Case Study in Business History. (Northampton, Mass.: Dept. of History of Smith College, 1951).

[164] Horowitz, The Morality of Spending, 120.

[165] Amy Hewes, “Electrical Appliances in the Home,” Social Forces 9, no. 2 (1930): 235–242.

[166] William Jenkins, “In Search of the Lace Curtain: Residential Mobility, Class Transformation, and Everyday Practice Among Buffalo’s Irish, 1880—1910,” Journal of Urban History 35, no. 7 (November 1, 2009): 985, doi:10.1177/0096144209347740.

[167] Cf. Andrew Gordon, Fabricating Consumers: The Sewing Machine in Modern Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012). As Andrew Gordon notes in his study of Singer in Japan, sewing machines were often not bought for utilitarian purposes; rather, they were frequently items of leisure or status. Wage-earning women probably weighed the costs and benefits of a sewing machine and, given their embrace of ready-to-wear clothes, decided that sewing machines were not a wise investment unless accompanied by an income-producing corollary.

[168] Green, Holyoke, Massachusetts: A Case History of the Industrial Revolution in America.

[169] The 1920 and 1930 census shows her living a 7 Clinton Avenue and 9 Thorpe Avenue, respectively.

[170] The census statistical abstracts break down foreign-born population by ward. The proportion of foreign-born residents living in wards 5 and 7 (combined) between 1910 and 1940 is as follows: 1910 – 13%, 1920 – 18%, 1930 – 22%, 1940 – 23%.

[171] Curran, The Parish and the Hill, 134.

[172] Curran, Parish, 95

[173] Relli Shechter, Smoking, Culture and Economy in the Middle East the Egyptian Tobacco Market 1850-2000 (London; New York: I.B. Tauris, 2006).

[174] Curran, “Paper City,” 48.

[175] Curran, The Parish and the Hill, 113.

[176] Ibid., 77–78.

[177] Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939 (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 135, 141, 330–331.

[178] Curran, The Parish and the Hill, 57.

[179] Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930: Abstract of the Fifteenth Census of the United States (U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1933), 450.

[180] Fifteenth Census of the United States.

[181] Curran, “Paper City,” 9.

[182] Mary Marconi, Interview of Mary Marconi by Chris Howard Bailey for the Shifting Gears Project, April 26, 1988, Center for Lowell History Oral History Collection.

[183] Paul Ellickson, The Evolution of the Supermarket Industry: From A&P to Wal-Mart, SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, April 19, 2011), 4, http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1814166.

[184] “Retail Trade of Holyoke, Mass.,” in Census of Distribution, 1930: Retail Trade by Cities, vol. 2 (U.S. Govt. Print. Off., n.d.), 3; “Retail Trade by Cities and Towns of More Than 10,000 Population,” in Census of Business (U.S. Govt. Print. Off., n.d.), 665.

[185] Marconi, Interview of Mary Marconi by Chris Howard Bailey for the Shifting Gears Project.