| << Previous -- Index -- Next >> | ||||||

| Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 |

CHAPTER VII

RIVERS AND ROADS

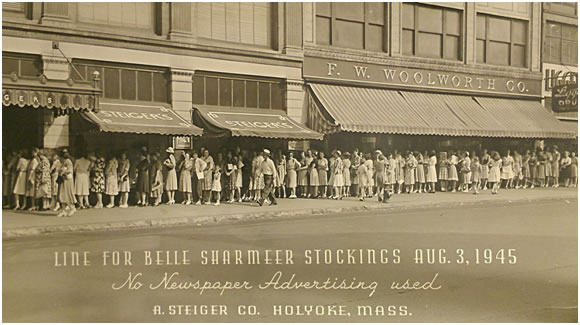

Figure 41: Line for Belle Sharmeer Stockings, High Street, 1945

“Harry ‘Moses’ Ludwig must be losing faith in his personal charms. He recently decided that a Ford was no longer a proper vehicle for his amorous adventures and has invested in a new Essex Coupe. More power to you, Harry.”

– Steiger Store News

When Underwood wrote Protestant and Catholic in 1957, he characterized the area of Main Street as the “old” business district, with “small hotels of ‘ill repute’ and itinerant lodging, of second-run movie houses catering largely to working people's diversions… clearly an area of deterioration, with former glories but a memory.” Underwood was effusive about High Street, however. It was “the central business district… major department stores and clothing retailers, the best restaurants, leading hotels and first-run, gilded movie houses” (Figure 41).[186] Underwood’s optimism would not save High Street in the following months. One year after his book was published construction began on a new High Street, farther up the hill.

Backed by the enormous investment of the federal government, Interstate 91 reoriented Holyoke once again, this time for the car, marking the death knell for High Street as cosmopolitan commercial center. The concrete, six-lane behemoth cut through a rocky outcrop just north of Holyoke in November of 1964. Contractors and engineers had no trouble dynamiting the shale until they became “slightly delayed by dinosaurs.” Ellen, from Paper City, would have recognized the fossilized tracks embedded in layered stone – in the book she sold them for a quarter a piece to tourists as a child. But this time they were holding up progress. Engineers had to wait for a month while paleontologists gathered samples. The contractors were not amused – progress halted by dinosaurs? Tourists came by the thousands to see the tracks. The new Mt Tom ski resort opened its slopes, even though there was no snow. “High up on the mountain were the skiers - going through their paces on a 200-foot-long carpet about 75 feet wide and made of plastic brushes.” The journalist noted that most of the 2,000 tourists were watching the skiers instead of the dinosaur tracks.[187] Once the dinosaur tracks were buried, Holyokers had before them an open road like never before, a high-speed pipeline to an infinite variety of consumer experiences – including a new Steiger’s store right off the exit (not to mention a plastic ski slope). I-91 offered direct access to the indoor Ingleside Mall. High Street was no longer the harbinger of the new capitalism; consumer capital moved on in search of new spectacles to sell, new space to occupy. In its wake, it left High Street and Main Street in the same predicament as the brick factories along the canals that moved to the South in search of cheap labor.

This study has argued that consumer culture changed Holyoke’s spatial orientation, atomizing working class practices and increasing their contact with “representations of space.” We have seen how a redesign of the park system, the influx of motion pictures on Main Street and the appearance of national brands in the Transcript-Telegram affected working class residents’ daily lives (Figure 19 and Figure 32). Streetcar lines spread the neighborhoods of the city across a wider swathe of land – breaking up communities and disassociating passengers from the industrial landscape (Figure 11). The dramatic spread of chain stores in the 1920s further atomized places where most Holyokers made their daily purchases of food (Figure 40). This study has also argued that the working class asserted their place in the city and created alternative spaces of their own, which resisted the threats that consumer capitalism imposed on space. The Grande Fête Jubilaire is one such example – its parade occupied the streets for celebration of French-Canadian survivance – not only on Main Street but also High Street. Furthermore, Mary Marconi continued to persist in ward 2, despite two evictions; she burned her credit records so her customers would no longer owe her, rejecting the values of consumer capitalist enterprises like A&P. Emma Dumas, much like scores of peddlers in the city who occupied the street corners and vacant storefronts sold in a way that confounded the homogenization of space and contributed to the persistence of ethnic enclaves, memory, and tradition. Anna Sullivan provided a space for free expression and assembly, thereby neutralizing the powerful influence that a department store owner had over his church and its communal spaces.

That leaves us with the two central figures: Jacques Ducharme and Mary Doyle Curran. Though Ducharme ends with continuance, survival and a return to an agrarian ideal, Doyle’s works end with death and loss. The conclusion one could easily make is that Ducharme’s optimism provides solid hope for continued French-Canadian survival, while Doyle Curran’s pessimism represents a surrender of Irish American identity in the black hole of “Money Hole Hill.” That simplifies the true meaning behind Doyle Curran’s novels. The description of the suicide of Billy in Paper City begins with the inevitable loss of his life: “When they reached the bridge over the rushing Connecticut, Bill said quietly, ‘I'm going for a swim.’ He stripped and walked nude to the high bridge. He dove like a sleep-walker, gracefully – like a bird flying free — free through the air. Joe stared frozen. Bill sank once, twice. Then Joe dove desperately, but it was too late.”[188] Tragedy, at first, seems the outcome of Billy’s death, but the concluding paragraph paints Billy’s jump as a form of emancipation. The final paragraph of the chapter reads: “And Bill, ‘child of sunlight, child of grace,’ who knows? Perhaps he will light in that golden sweet apple tree and sing as sweetly, fly as freely as he had dreamed – a golden bird, a bird of light – a morning bird, a bird of grace – free now of both time and space.”

Thus, the river, not a rosary, serves as Mary’s central symbol. Billy’s jump into the waters, which frees him from time and space could be contrasted with Pierre Delusson’s yearning for “distance and space, color and movement”[189] For Doyle Curran, the river is where working women managed rows of vegetables and kept cool picnics on the banks – a place she yearned to visit from the sweltering heat of “The Hill.” The river is variously associated with darkness, the past, tradition, memory, and it is where unwanted things go, such as Mary’s beaver skin cap, old crates, and old rowboats. But the river is also a form of life and renewal for the Paper City; as Ellen retreats from the waters, she grows more nostalgic and morose. Death appears at the cemetery at the top of the hill, just as often as it does in the river. Is death a negative thing in Mary’s eyes? In Parish it is an opportunity for Mary’s mother to bond with the community through wakes.[190] Mary begins every chapter in Parish with “I remember,” an affirmation of the river’s interminable flow which continually replaces old memory with new – a ritual that does not end with the death of her grandfather in Parish. J.B. Jackson writes that the “golden age,” a time when the past had an innocence and simplicity “begins precisely where active memory ends - thus about the time of one's great grandfather.”[191] It is no wonder that the limit to Mary’s connection with her identity centers on her grandfather. New memories accrete with old ones while other bits recede away. In the context of architecture, Jackson sees this as a necessity: “There has to be an interim of death or rejection before there can be renewal and reform. The old order has to die before there can be a born-again landscape.”[192]

Walk along Holyoke’s Main Street and you will pass the forlorn, collapsing ruins of Mary Marconi’s market. The Bijou theatre no longer exists, and the union hall where Anna Sullivan hosted Margaret Sanger has been replaced with a parking garage. There are no A&Ps left in Holyoke, and the Transcript-Telegram folded in 1993. Both department stores downtown are closed. The enormous frame of the Hotel Nonotuck, where Albert Steiger envisioned a new center of commercial leisure, stands empty next to the vacant 2,300-seat Victory Theater. Mt Tom Resort is a charred foundation. These sites have died as consumer space, but they remain as genius loci for those who still endow them with meaning. “I saw the dead lying stiffly in their graves,” Doyle Curran writes in Paper City. “I thought, they will rise lightly again from those graves. The broad river ran swiftly over the dinosaur tracks, and slowly the paper city tumbled into darkness.” Sullen as this ending may seem, the humble symbolism of her syntax points to the future. “I thought,” she writes of the dead and forgotten – separating this initial clause with a comma to highlight the declarative, “they will rise.” So with the inundation of dinosaur footprints and darkness descending on Paper City, Doyle Curran anticipates dawn and receding waters ahead. She may not point to a “New Basis of Civilization,” but Holyoke’s spaces and its streets – the ruins of consumer culture – face the possibility of being reincarnated as arenas of communal participation.

| << Previous -- Index -- Next >> | ||||||

| Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 |

[186] Underwood, Protestant and Catholic, 196.

[187] Michael Strauss, “A Prehistoric Tourist Trail,” New York Times, November 22, 1964, sec. Resorts and Travel.

[188] Curran, “Paper City,” 137.

[189] Ducharme, The Delusson Family, 156.

[190] Curran, The Parish and the Hill, 67.

[191] J. B. Jackson, The Necessity for Ruins: And Other Topics (Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1980), 100.

[192] Ibid., 101.