Treatise on Trespassing

By Jonathan H

Consider this a manifesto of sorts — an encouragement to go beyond the societal definition of private property and pave your own way. You should do this because these places are disappearing. You should do it because through your stories, and your experiences, you could perhaps inspire us to appreciate history for its lessons. Do not let old laws prevent you from telling incredible new stories. Do what you believe is right, rather than what the establishment says is right. There is still much to discover in this world. It all may seem to become less mysterious by the day; in reality, each day brings a new thing to analyze and a past to appreciate.

I wear shoes with padded soles to these places of the past; this keeps me from being heard while walking. Touring an abandoned place is a lot like walking through a post-apocalyptic no-man’s land; but with it comes both the guilt and exhiliration of potentially being caught for a crime.

When we see these places from the outside, they often don’t leave us with any lasting impression. Passing by them may incite idle curiosity for a few fleeting seconds, but it’s generally in passing. When one is inside, though, the experience changes. There are moments in which I’ve heard my own heart beating; seen flapping gulls in a framed-glass six story foyer that once housed radioactive ship components; an escalator that was once the world’s tallest and sits covered in mold, rust, and bird droppings. In a digital age, where everyone has a camera and every person with a cell phone is a photographer, these places serve as ideal snapshot fodder — and as a result an entire sub-culture of explorers have built a veritable institution online.

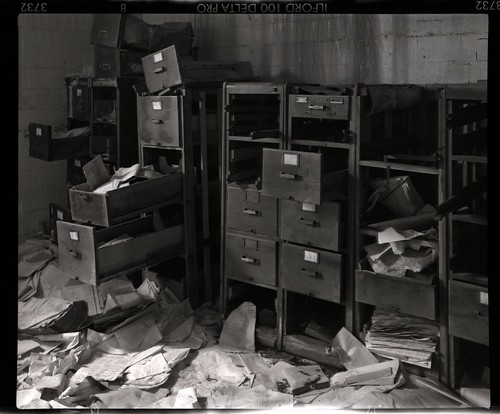

Beyond their raw photographic, draw though — beyond the interplay of light and rust, peeling paint, and the odor of asbestos and death is something that tells more about our culture than any critic or pundit could. Top secret manuals strewn about in military bases closed by the Base Realignment Committee; a multi-million dollar mansion built by a copper baron; the pervasive smell of benzyne, diesel fuel, and who-knows-what-else hundreds of feet underground in a Titan 1 missile silo. These experiences are incredibly formative; in an odd way they are the modern, post-industrial equivalent of Muir’s cathedrals.

My first conversion experience was not in a pew; it happened while I was alone. I was about to enter one of Oakland’s grandest historic structures — the Key System building. Pulling up a retractable ladder to a second story window, I nonchalantly climbed into the dark hole as bus passengers across the street looked at me in shock. The ladder disappeared from the bus passengers’ view along with me as I cautiously strolled across the precarious platform, which had a commanding view of the lobby below. Hand-carved Beaux Arts plaster had toppled from the ceiling; water dripped; a lone desk from the 40s sat in the middle of it all, rusting in its wake. But the conversion came higher — six stories up. I climbed the wrought iron staircase, encountering artifacts from various raves dating to the 80s. Though the building was an empty shell, one still had a sense of its magnificance. It was first built as a bank building and the architect spared no expense.

As I went higher, the rooms became emptier. Characteristic orange sodium vapor light flooded in through the broken windows. A building’s beauty is often best brought out when it’s empty. All too often we walk through active buildings and take little note of the care that is taken into its construction. At night, and while empty, is a building’s moment of glory. If a building’s best moment is when it is empty, its worst moment is reaching the final set of stairs. It is a moment of loss; a moment when one realizes there is nothing left to discover and this brief escape — like all escapes — will have its end.

I emerged to the roof and saw high-rises all around me. To the north was the Tribune building. I stood there to take it all in, understanding history through experience; knowing what a place once was, in the middle of a growing city that’s so alive, yet still carries the dead weight of the past on its shoulders. I stood there for what seemed like minutes (likely hours) in meditative silence. There on the top story of a 1911 building, a new belief was formed, and since then have discovered things about the past that few have been privileged to see.

Yes, I am a trespasser, and I have likely encroached on one of America’s dearest of ideas — that of private property. But through that minor transgression, I have been in the captain’s room of a 1950s cruise ship and have seen the silo of a 4-megaton nuclear warhead; photographed the abandoned mansion of a billionaire, and walked the halls of a World War II secret interrogation facility. It’s good to know there is still much to discover in this world, and taking pictures of these places is my conceit of ensuring that they’re never forgotten.

Reddit!

Reddit! Del.icio.us

Del.icio.us Digg

Digg StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Technorati

Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl

i am a rookie to trespassing with my camera. but you put into words the reason i started my blog in the first place: “taking pictures of these places is my conceit of ensuring that they?re never forgotten.”

although not all of my discoveries are forbidden or frowned upon, my intent is still the same. if it means i have to hop a fence or pry open a window, so be it.

regardless, thank you for writing this. and thank you for your work on flickr. you have inspired me to get to know The City on a much much more initmate level.

Heavy, man….heavy. Nice words!

Nice! Now I know how you got those great Sugar Factory pictures. Was just over there the other day.

Jon,

It’s interesting that you tie the concept of trespassing with the American value of private property. Although I agree with the connection, it seems that nobody knows who really owns many of the properties that I’ve considered trespassing on. It’s not like I’ve (considered) trespassed(ing) on someone’s farm or in their house. But there may be an old resort hotel (we think it’s owned by a developer, but we don’t know where they’re located), an abandoned Naval communications base (we can’t be sure if the county owns it, or if they’re just holding it for the federal government), not to mention all of the neglected government property (is that private, or public)?

I wonder if other people who consider trespassing try to rationalize their actions the way I do (that is, if I were to ever trespass, and I’m not saying I do, and if anyone says I did, well maybe they just thought I did).

Andy

Andy, you make a really good point that I wish I had elucidated in this piece. You’re right — much of the grasp on these places is tenuous at best. The supposed “owners” are developers, corporations (who are considered people according to the IRS and Government), and bureaucracies that number thousands of technocrats… they are not individuals… they are not the ‘Jeffersonian’ landowners.

I’ve never really thought seriously of trespassing in someone’s house… well, scratch that… I’ve done it many times, but only in an instance when the owner is so incredibly filthy rich that the mere object of their ownership should — in all intents and purposes — be owned by the common or be accessible by the public in the very least. (others will disagree with me on this, I’m sure). And only if said house is left to rot, when it clearly could be put to good use for the general public.

I think we, as a country, and as humans (not just Americans) have not fully put into writ the proper use of space. Private property is a very dear idea, but it could all too often become something that oligarchs love to champion in order to consolidate power.

Still, I think much of what we explore as historians, landscape speculators, lovers of all things built — the things we appreciate should, by proxy, be publicly owned. But maybe that’s just my bias speaking 🙂

Nice piece Brother Jon, can I get an amen, somebody!

A few comments:

It’s refreshing to see an urban explorer using his real name when talking about trespassing, something every UE’er does, yet rarely admits to. I admire your frankness.

Yes, most of these places are lapsed, unattended and forgotten, without a caretaker in sight. However, you and I have both been to many of the same places. We both know that had we been caught in them, there would have been hell to pay. Fines, “film” confiscation and even possible arrest.

I get e-mail almost every day from people wondering about trespassing aspect of the places I explore. Many of them are “Too scared to risk it.” I think that’s good. UE is not for the risk averse. People that have reservations about sneaking through a fence need not apply.

Conversely, it’s easy to become too cavalier about it. It’s one thing to trespass on abandoned, toxic and dangerous military/industrial complex ruins yourself, but it’s quite another to encourage the public at large to do it. What we do is dangerous and illegal. We come prepared, we understand the ramifications of what we’re doing. I’ve had e-mail from someone who went to Byron because of my photos and got caught by the sheriff and had to pay a $300 trespassing fine. I won’t come right out and say it made me feel guilty, but it sure made me sit back and think about what I say to people who enquire about locations.

So yeah, just get out there and do it people, but don’t come crying to us if things go horribly wrong.

Troy

Thanks Troy! Another fine comment, and incredibly, I seem to agree with it (this doesn’t happen too often). I don’t encourage people to put themselves at risk. I think what I personally believe and encourage people to believe, is that they should — in a more general way — not let the rules and regulations rule their life. Of course, they are there for our own protection, but sometimes the best thing a person could have is to be deshackled from such protection in order to find their own way around.

Troy, you’ve been an inspiration to so many people. The fact that one person suffered a minor arrest is a small price to pay for the amount of cultural and historical awareness that you’ve helped inspire. What you do, and many of the other landscape artists have done, is integral to how people perceive the things around them. I can’t wait to see where this goes. I’m happy to be here to see it happen.

I think I want to marry you. Phenomenal pictures and amazing language use. Thank you for being awesome.

I’ll give that Amen. So well said, Mr. Haeber!

Hello! I am a big fan of urban exploration, and of photography, so when I stumbled upon your site, I immediately subscribed to the feed 🙂

A couple of months ago, I was asked to do a photoshoot with a local industrial band. I do it for free for them because I am an amateur and because I am a fan (and it doesn’t hurt to get experience and a portfolio for posterity). The band chose the site this year (I had found a shooting range in the desert last year, which worked because they were doing a post-apoc theme at the time). This year, it’s steampunk, so we all went out to this seemingly abandoned industrial site on the edge of Phoenix. I couldn’t tell if it was an old cattle ranch because there were huge silos and gigantic pipes and machines with guages and gears. My photographic utopia! There was so much rust there that I couldn’t take enough photos during that session. I will have to make the hour trip back out there to get more before the city reaches the site and tears it down to build suburbs, walmarts and home depots.

Anyway, just wanted to share some photog love 🙂

Oh, one thing I identified with in this post was the fear of being caught. We had around 10 people out there, talking at full voice, our cars parked right in front of the site, and no one bothered us. Maybe we were lucky. Maybe anyone who may have seen us just didn’t care. We also passed a dam which looked like it had been deliberated broken. There were pillars standing there, supporting nothing. Also, there was one of those 2 lane steel bridges. Scary to drive on, but oh so beautiful!

Thanks for the stories, Alex. I appreciate the good words, and I’m looking forward to hearing more about your future explores.

Pingback: Why I Explore Abandoned Places and Why It’s Insane - Bearings