Colorado Sugar Beet History & Architecture

Show on map October 20th, 2007

Show on map October 20th, 2007

By Jonathan H

The Longmont Sugar Refinery, once one of the Great Western Sugar Company’s largest factories — shuttered in 1978 (photo copyright Jon Haeber).

Editor’s Note: Yes readers! Once again, I’m bringing you a special series. This one’s about the sugar industry in Eastern Colorado. There are three parts. This is part one. Stay tuned for parts two and three. Enjoy!

In Colorado there is a linear north-south collection of abandoned skeletons following the railroads outside of Denver. These brick edifices are decaying reminders of Colorado’s agricultural renaissance. Bricks collapse from four-story parapets and railroads are buried in weeds and detritus, but behind the decay and overgrowth is the history of the greatest sugar magnate in American history: The Great Western Sugar Company.

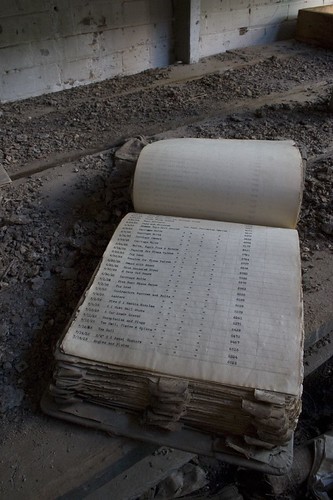

This is a ledger book from the Great Western Sugar Co. Eaton factory. Eaton is named after the tenth governor of Colorado, Benjamin Eaton, who was instrumental in getting the irrigation infrastructure set up that would later serve the beet industry well (photo copyright Jon Haeber).

These massive brick buildings are like nothing I’ve seen in my life. Early in Colorado’s history, the vast expanse of barren land was considered a desert. Famous New York Times Editor, Horace Greeley, described the Colorado plains as a “land of starvation.” This didn’t stop Greeley from endeavoring to establish a utopian colony there. His plan funded the beginnings of place of high moral standards and temperance. Never one to shy away from self-promotion, the utopian colony was named “Greeley.” After the Land Grant Act of 1862, thousands of families flocked to the Colorado plains in search of land worth subduing (in a biblical sense).

At first, wheat was the cash crop, but disaster stuck in the 1890s when the price of wheat plummeted and this bread basket of America needed a new boon basket — beets would be Colorado’s salvation. By 1900, there were brick buildings arising to process the growing influx of beet from the fields. The citadels of these towns had become tall, brick smokestacks spewing steam and spitting out refined sugar.

The Ecology of Growing Sugar Beets

There are only a few places in the world perfectly suited for the sugar beet horticulture. Sugar beets require a specific balance of light, minerals, and water in order to produce a minimum of 12% sugar content by mass — and this balance must follow a specific seasonal schedule. The plains along the Front Range of Colorado had this balance unlike anywhere else in the world. In fact, the balance was so perfect that some areas featured an alarming 17% sugar content by mass.

A young man sits near a truck bed stacked with sugar beets from Northern Colorado, ca. 1915 (courtesy Denver Public Library)

All the Front Range needed was water. That’s where Benjamin Eaton had come in. As a massive landowner, he served as one of Greeley’s first officers of the utopian Greeley colony. Eventually, though, the utopian vision was thrown out the window and dollar signs began appearing in the eyes of the capitalists.

The American Sugar Refining Company headed by robber baron H.O. Havemeyer had incorporated in 1891. Local growers of the utopian proclivity began to accept the capitalist emergence. So says the Jan 15, 1903 New York Times: “It is believed in Colorado that the American Sugar Refining Company has acquired such a large interest in the beet sugar business, either directly or indirectly, that it controls it.”

By 1903, the capitalists had thoroughly gained their ground, and thus the vast amount of money necessary to build the factories flowed in. The factory in Longmont was designed and built by the Kilby Manufacturing Company of Cleveland, Ohio. The bricks for it were provided by contractors Edward Seerie and Frank Hill of Hill & Seerie — who also provided the bricks for Denver’s Sough High School. Longmont Sugar cost one million dollars to construct — an astronomical sum for any project in the early 1900s.

Construction of the Longmont Sugar Refinery, ca. 1910 (courtesy Denver Public Library)

Only two years after construction, the newly formed Great Western Sugar Company had taken over the Longmont factory. In a few years time, the company had retained control of 15 factories along the Front Range. By 1920, Sugar was Colorado’s mainstay — the value of its harvest had multiplied to 20 times its 1900 level.

Please continue following Bearings, or subscribe to its RSS in order to continue following the incredible story of sugar in Colorado. Stay tuned for parts two and three.

What came from the war was a vast network of powerful communication hubs. During the war, these hubs were under the control of governments like never before. Unique to the U.S., when compared with other allies, was its insistence on holding on to influence over these radio holdings. Wireless had gone from a “mere adjunct to visual signaling” to a vital factor upon which armies, navies, and air forces had relied (Baker 177).

What came from the war was a vast network of powerful communication hubs. During the war, these hubs were under the control of governments like never before. Unique to the U.S., when compared with other allies, was its insistence on holding on to influence over these radio holdings. Wireless had gone from a “mere adjunct to visual signaling” to a vital factor upon which armies, navies, and air forces had relied (Baker 177).