Bethlehem Steel, Wartime Labor, and San Francisco

April 12th, 2007By Jonathan H

By Jonathan Haeber

Union Iron Works, headed by Irving M. Scott, had become a major war contractor leading up to the Spanish American War and the occupation of Hawaii in the 1890s. Dogpatch was filled in with rock by the railroad companies and Pier 70 became Union Iron Works’ center of operations.

Part 1 — Union Iron Works, the New Navy, and Portrero Point

Editor’s Note: This is Part One in a three-part entry on San Francisco’s Dogpatch and Pier 70. The series follows the organized labor history of the Gilded Age’s most influential industrialist: Charles M. Schwab and his Bethlehem Steel.

It was once a small promontory on the southeastern edge of San Francisco — an outcropping of California’s state rock that would eventually be razed for a working-class ‘company town’ known as Irish Hill. A short walk to the north was Dogpatch, a marshy no-man’s land until a few powder works moved in to provide gold mines with much-needed explosives. The railroads followed, and soon a bridge was built to cross the swamp.

Dogpatch was the center of San Francisco’s Imperial Age industrial might. Out of a swamp arose Union Iron Works. It had grown from a small forge producing stamp mills for gold mines to the largest ship builder on the West Coast. Throughout its history, the story of labor is inextricably bound to the site of Union Iron Works. According to Christopher VerPlanck, “no other district of California was industrialized to the degree of Portrero Point during the last quarter of the 19th century.” In this rough area of industrial San Francisco we see the perfect example of war’s inextricable connection to organized labor. Seen from the surface, labor may benefit from a wartime economy, but in general it stymies organized labor and ensures the governmental regulation of labor organizations. A prime example of this is told through the legacy of Charles Schwab and his San Francisco shipyard.

Irving Scott’s Union Iron Works started as a Gold Rush company but really grew big on the business of American Imperialism.

In the 1880s to 1890s the U.S. Navy experienced incredible growth in its fleet — so much so that it became known as the “New Navy.” The impetus for growth was primarily due to the U.S. interests in the Pacific (particularly Hawaii) and the looming overthrow of Hawaii’s Queen Liliuokalani, which would provide a perfect port for U.S. naval occupation. By this time, Union Iron Works was no stranger to shipbuilding and Irving M. Scott knew that the Navy would need frigates on the West Coast. Scott secured the first Navy contracts for Union Iron Works, which would help it become “the largest shipyard in California and the dominant manufacturing facility on the West Coast” (VerPlanck).

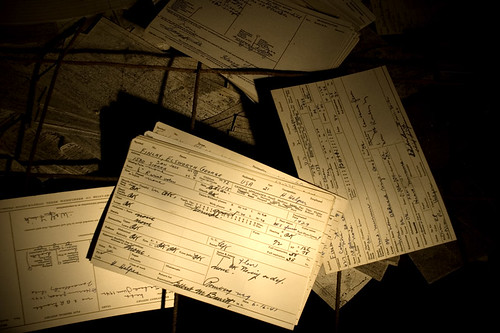

Employment health cards in the basement of the 1896 Union Iron Works administration building. Each card lists physical descriptions (including euphemisms like: “fat, thin, slovenly, lethargic, pale, nervous, wiry, muscular”). They have the home address and the name of the steelworker, their heart condition, their scars — there’s even an eerie column for “missing parts” (perhaps an indication of the danger of the line of work they were in). There had to be over 20,000 sheets in the pile. A neatly stacked historical record that probably won’t survive another 20 years simply because of its volume

In the 1890s labor at Union Iron Works was not organized. The IWW was yet to be born. AF of L was just barely getting started in Ohio, and had bigger fish to fry than Union Iron Works; its principal target was one industry becoming a major player: Steel. At the head of these newly rising big businesses were industrial giants such as Elbert H. Gary, Andrew Carnegie, and a young entrepreneur — Charles Schwab. Schwab had helped catapult Carnegie’s U.S. Steel into success, but he had a tenuous, often fiery relationship with labor

?

?